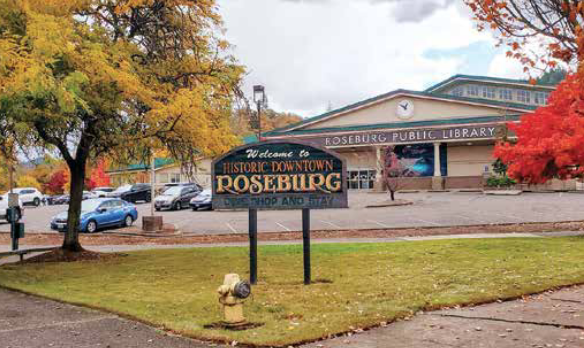

In November 2016, Douglas County, Oregon, voters rejected a modest $70 per household tax increase that would have supported the county’s 11 libraries. Six months later, all 11 libraries closed their doors with no plan or mechanism for reopening. Roseburg Public Library, about 180 miles due south of Portland, the last one was closed on May 31, 2017.

With a population of 25,000, Roseburg is the largest city in Douglas County. Roseburg residents had agreed to the tax collection and were upset at the loss of their library and the prospect of becoming part of another American “book desert.”

Book deserts are a major problem for much of America’s rural communities. In general, book deserts arise in areas where there are few or no libraries or bookstores. remedies such as Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library Help, say proponents, but such programs are usually aimed at a select audience: children up to the age of five get free books sent home. And push-in solutions like these are usually designed to bolster, not replace, existing libraries or public schools.

In a country where so many rural communities are struggling to pay their bills, the emergence of book deserts is a major impediment to progress, including in Oregon. While many consider Oregon to be politically progressive, this is only true of the cities around the Willamette Valley. In fact, outside of the I-5 corridor, much of Oregon’s population tends to be libertarians and often wary of taxes. Oregon’s population is also scattered over a vast tract of land where having a library building or bookstore nearby is often not an option.

That’s why the successful solution that Roseburg City Manager Lance Colley, with help from Douglas County Educational Services Department (ESD) Superintendent Michael Lasher, developed is a ray of hope for millions of people who could suddenly find themselves living in counties without access to the public library. Taking their own constituents’ approval for the county levy as a mandate to reopen their local library, Roseburg leaders went to work on their behalf.

“Our library is 30,000 square feet,” says Colley. “You can’t rely on volunteerism to run that.” He notes that “seven or eight” other libraries in Douglas County now operate entirely on volunteer work for limited hours. At least two Douglas County libraries have been without lights since 2017. Nearby Josephine County, just south of Roseburg, defunded all of its libraries in 2007, and for a decade its libraries were staffed by 360 volunteers. This was not the case until 2018, with donations from 2,000 people and three attempts to ensure stable financing through taxes the Josephine Community Library opened again. Roseburg faced a similar struggle unless a solution was found quickly.

So Colley approached Lasher with an idea. ESD needed administrative space, and ESD and the library could jointly fund a renovation that would allow the library to reopen, this time not as part of the county system but as a city-funded facility. But even with the ESD on board, the city still had to fund 66% of the library’s budget. So Colley was busy reaching out to local philanthropists and won several five-figure grants from the State of Oregon, raising a staggering $750,000 in five months.

“Roseburg is one of the most charitable communities in all of Oregon,” notes Colley, “run by the Ford Family Foundation [a private nonprofit headquartered in Roseburg]who have been very supportive of the project. Kenneth Ford and FFF were instrumental in building the library over 20 years ago.” CHI Mercy Health, the Cow Creek Tribe of Umpqua Indians, the Collins Foundation and the Bruce Family Foundation also made appearances.

Colley secured another grant to furnish the library, and a local wholesaler supplied all the furniture. Colley credits library consultant Penny Hummel with particular expertise. And Director Kris Wiley was brought in from Minnesota six months before the reopening to prepare the new library for its patrons.

Less than a year after raising the funds, the Roseburg Public Library celebrated a grand opening in January 2019 – this time as a public library. The entire Roseburg community and librarians from across the state who had helped Colley revitalize the former district library came to celebrate.

Wiley says most of the heavy lifting was done by the time she arrived, allowing her to focus on the details. Of course, taking care of the details was no small matter, considering pandemic lockdowns forced residents out of their new library just 15 months after its grand reopening.

Under Wiley’s direction, the library delved into digital lending during the pandemic and created a guide to using OverDrive’s Libby app to help users access the Oregon Digital Library Consortium’s 66,000 e-books, journals and audiobooks that are available for access.

Like many libraries, Roseburg hosted virtual events, classes, and weekly livestream stories in English and Spanish. Librarians also gave out 500 take-home craft bags and thousands of books at the curb, and lent out more than 48,000 items in total in 2020 and 2021 — a whopping 62% of the total library collection. In 2020-2021 alone, when people were in isolation, the Roseburg Public Library saw nearly 132,000 visits.

Residents of Douglas County outside of Roseburg can continue to use the Roseburg Public Library for a $60 annual fee. However, the fee is waived for all youth residing or attending school in the Roseburg School District, including children who are homeschooled or attend private schools. Individuals participating in nationwide food aid programs can also use the library for one year free, a program funded by donations.

In 2018, Colley told a local reporter he was planning to retire after 35 years of public service. He was looking forward to spending more time with his three grandchildren and a fourth was on the way. But when the library closed, he decided to stay. He just couldn’t leave his town without a library.

“A small group from one of our elementary schools invited Michael Lasher and I to speak to their class about reopening the library,” recalls Colley. “The students have all written us notes thanking us for taking on this. That was before we started fundraising. We heard from second, third, and fourth graders the importance of having a public library that they could go in and borrow books from. A little girl, almost in tears, asked, “Will you have encyclopedias? We can’t afford to buy encyclopedias.’ That made a big difference for Michael and I.”

Kathi Inman Berens is Associate Professor of Publishing and Digital Humanities at Portland State University in Oregon.

Return to the main feature.

A version of this article appeared in the 7/3/2022 issue publishers weekly under the heading: From the book desert to the oasis